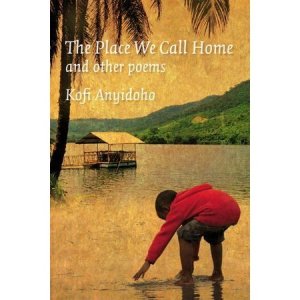

Title: The Place We Call Home and Other Poems

Author: Kofi Anyidoho

Year: 2011

Reviewer: Kwabena Agyare Yeboah

The Place We Call Home and Other Poems is the sixth poetry collection of Kofi Anyidoho, one of Ghana’s foremost poets. It is his second collection after close to a ten year hiatus. This break would have a profound effect on the poet. During that period, he went back to researching into traditional poetry of his people – the Anlo-Ewe. Yet, his return with PraiseSong for TheLand (2002) is unlike Elergy for the Revolution (1978) and A Harvest of Our Dreams (1984) which imitate the dirge, halo and other traditional song forms on page. Anyidoho is a traditional poet and of change.

The collection is divided into three movements. Movement One opens with a prelude. It invokes Husago and Misego. Husago also appears in PraiseSong for TheLand (2002). Husago is ‘’an introductory dance to all Yeve (diety) ceremonial dance-drumming . . . to alert all members of the society to the commencement of the rituals.’’ It is a forward-backward-forward dance. Misego is a variant of Husago.

In some of Anyidoho’s previous books, he recycles ‘’birth-cord.’’ In the more traditional past, his people buried the after-birth of twins and planted trees on them. Towns and villages were founded on them. This was how they were connected to home or the idea of it. In a literary sense, it means generations of artists. Newer folks should be connected with older folks like fetus and mother. It is bridging the gap between the past and present.

Here, birth-cord is replaced with Husago. It is re-thinking how the past connects with us, the present. Like Sankofa, the Akan aphorism, Husago teaches us that we should go back to the past to gather the selves we left behind. The categorization is actually a mimicry of the steps of Husago. Forward-backward-forward. Or, backward-forward-backward. The collection of poems is a performance of Husago and we, the readers are part of a society, a select few of those who believe in the power of words, who are called to witness the commencement of a ritual – of home-going and home-coming. It is an extended metaphor.

Anyidoho always re-members a group in his collections. It started with Vida Ofori, Adjei Barimah and others students who died in student protests in the late 1970s to mid-1980s in Elergy for the Revolution (1978).

Movement One. Backward step. The first two poems are chants that precede the performance (like call to worship). This section of the recollection recalls history of the African continent. It reads like a poem from Ancestral Logic and Caribbean Blues (1992).

Movement Two. Forward step. This section deals with geopolitics of war. It carries forward a voice that expands the definition of ‘’my people.’’ It defiantly places Africa on the discussion table to talk about what a superpower is doing wrongly in the world. It re-imagines powerscape.

Movement Three. Forward and Back steps. This section tells varying reflections of the poet-persona. It is a mature voice that has grown to appreciate and accept certain realities in life. It does not fight nature. It accepts time.

I wanted so much to hand over

blueprints for endless future plans (Post-Retirement Blues, p. 83)

But

in my haste

to embrace Eternity on Life’s High Ways

I forgot I overlooked Old Time

still lurking among the AlleyWays (Post-Retirement, p. 86)

At the heart of the collection is the question of home. Where is home?

I will come again to these Shores

I must come again to these Lands (The Place We Call Home, p. 31)

These lines contest the idea of home. It makes it global and it disrupts it. Home is where you are and it is a fantasy.

In Wellington once I watched the Maori

dance and sing the loss of Ancestral Lands Gods

From Medellin of the Distant Dream

to Baranquija on Colombia’s Carib Shores

In Santiago de Cuba of a Troubled Hopeful Time and

in Haitian nightmares of Santo Domingo

I saw I heard I felt I smelt I even tasted

a trail of Blood across our History’s Final Sigh. (The Place We Call Home, p.31)

Home is memory.

There is something about The Place You Call Home:

Something about familiar contours of The Land

about the very Tate of Air

that essential Smell of Earth

something about the very Feel of Things

the Geography of Lost Landmarks

the Chemistry of Fond Memories

even about the Nothingness of Time

Home is nostalgia.

the termite eaten face

where often you stood

on One Leg

trembling holding

your breath for a Lover

now lost to Childhood Dreams.

This poet is mythmaker. He does it with words. He creates his own words by randomly capitalizing common nouns and/ or joining any two of such words. Those happen anywhere in the sentences. This is the rebel-poet we know. He is innovative with space; they replace commas. He gives the reader the chance to make the work her own, reading at her own pace with no guidance whatsoever. When you read them, you give them a voice that is your own. Perhaps, we should rethink what we think is the meaning of ‘’my people’’ that he often uses. It should be politics of global inclusion rather than exclusion.

………..THE END OF A NEW BEGINNING……..

That’s how he ends it all.

But Ah! The Glory!

The FearSome Glory of This Life….! (But Ah! The Glory!, p. 88)